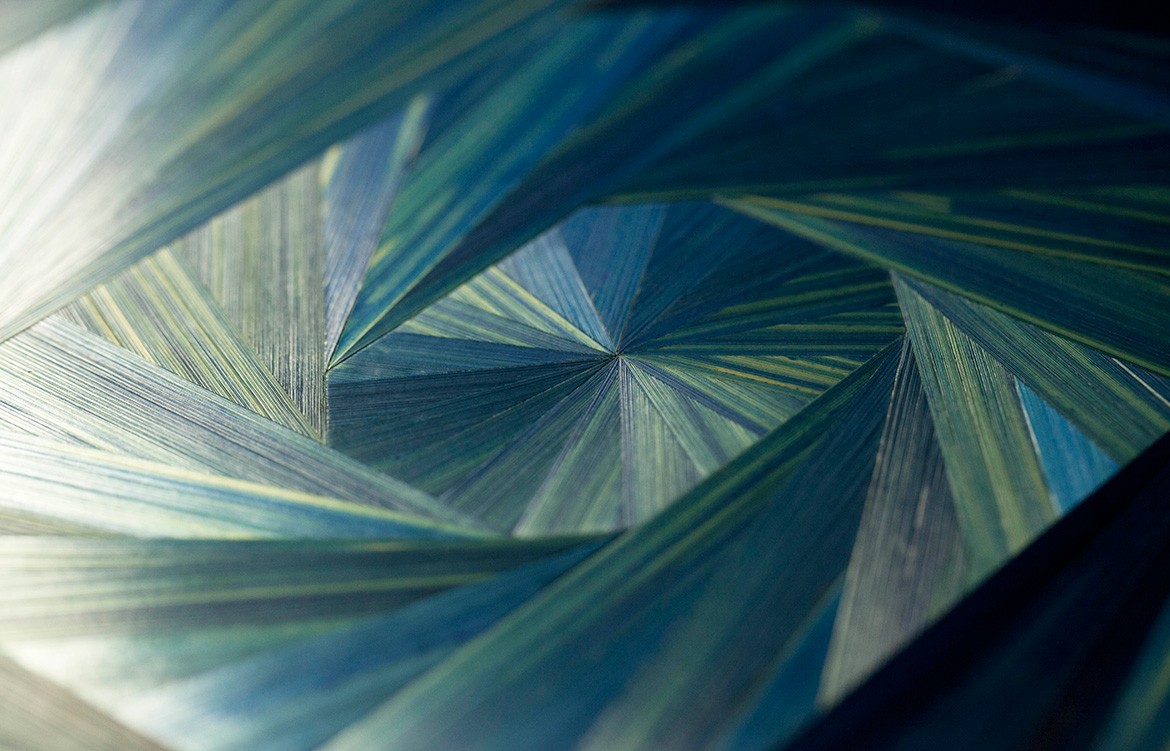

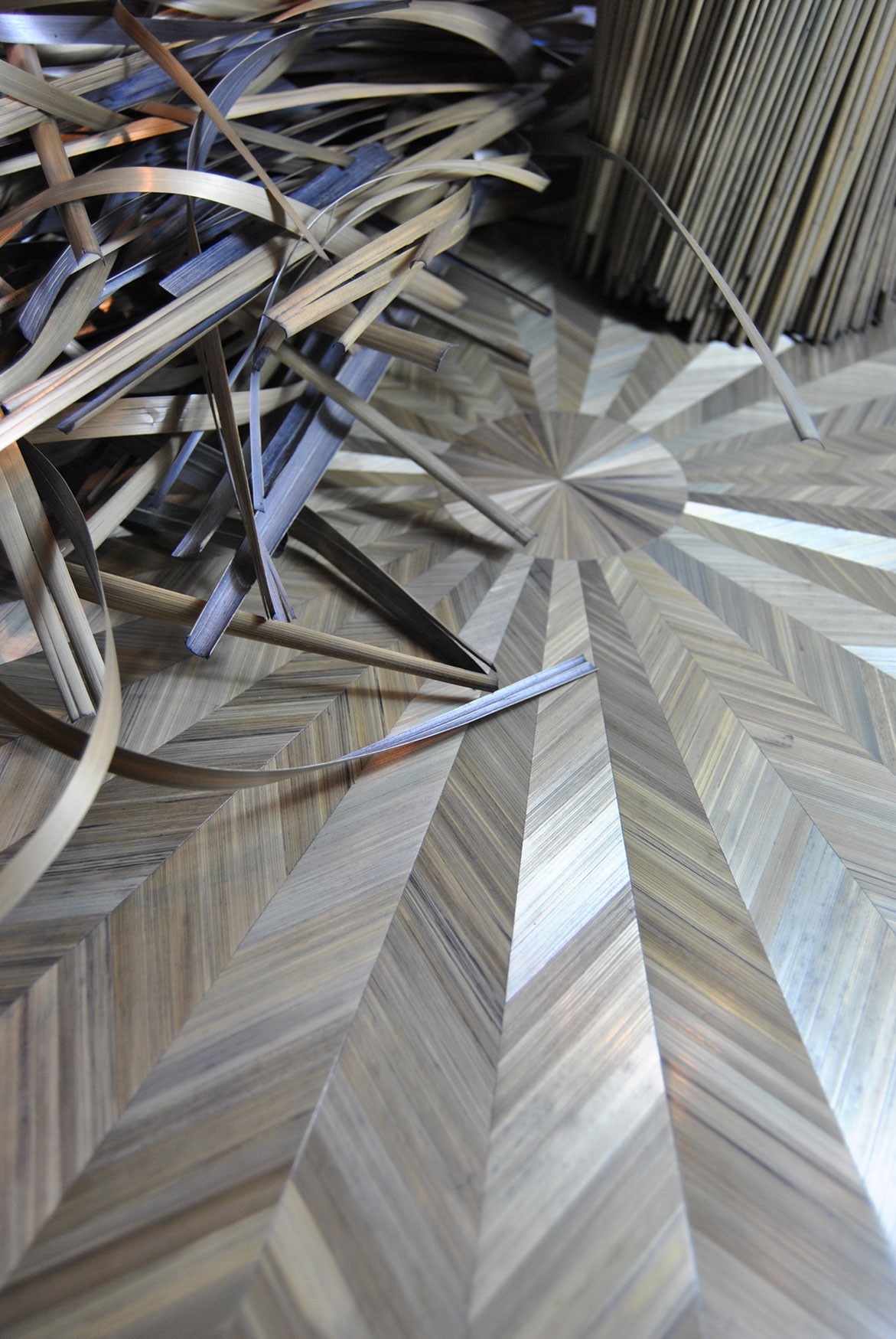

Deep within a ramshackle warehouse building is an unassuming Frenchman splitting straws and glueing them onto furniture. It’s not as rudimentary as it sounds. He’s one of only a handful in the world still practising straw marquetry and his pieces sell for thousands. The material isn’t valuable and the skill is, by his admission, fairly straightforward, but the time it takes makes for a precious commodity. As with the craft of passementeries, this method of decorating furniture is cost-ineffective and few are willing to pay the resulting value, especially when our idea of ‘value’ has been so warped by the era of cheap mass production overseas.

Arthur’s father, Jean-Luc Seigneur, is another champion of an old craft: a rare embossing and hot stamping technique, and his own experience represents the downward spiral of the handmade. He established his workshop in 1979 near Bastille, Paris, but has slowly been pushed to the outer suburbs, forced to fire his team one by one until he was left on his own, despite collaborations with major luxury brands. He remembers the era when designers started to become more obsessed with making income than making things of beauty. He still collaborates with decorators, artists and artisans and watching him in action is an inspiration.

A resurgence of the handcrafted is building momentum, so will that equate to a change in buying behaviour, which might, in turn, allow sole traders to hire young apprentices and keep their craft alive? Arthur’s recent collaborations in Australia tell of a demand from the upper echelons of interior design: Thomas Hamel, Burley Katon Halliday, Nina Maya, Jason Mowen, James Salmond and Adam Goodrum to name a few. He sees his future as creating more artworks than furniture, explaining that people are more willing to splurge on art.

Arthur learnt straw marquetry in Paris from Lison de Caunes, a family friend whose grandfather, designer André Groult, had dabbled in it himself during the craft’s Art Deco revival, and had bequeathed her his stockpile of straw. Lison has single-handedly revived the craft in France and her mission shows what can be done with a personal investment in preservation. Arthur has had the occasional notion to teach his skills to young Australians (who often turn out to be French expats). He’s found trained bookbinders seem to pick it up most effectively. There’s another craft we’re in danger of losing.

Could some of the Gen Y and Z-ers who apply for ‘internships’ on Pedestrian TV and work for anyone for free doing anything be gently beckoned away from the overflowing digital industry and into Arthur’s workshop? Same lack of pay, but to become ambassadors of a centuries-old craft rather than digital minions.

The revival of some ancient crafts via forward-thinking designers suggests we’re entering an era in which this wouldn’t be an impossible notion. British designer Simon Hasan’s work walks the line between ancient crafts and industrial design, practising what he calls ‘design archaeology’. For years he’s crafted leather furniture using a medieval technique once used to make armour, which alters the tannin and collagen fibres in the leather to make it rigid and structural.

Ceramicist Joe Darling of The Pottery Shed, whose hand-throwing classes just keep getting bigger, has faith in our “natural balance” and believes we just won’t allow heirloom crafts to be rendered obsolete. Sydney-based stonemason Ted Higgins too says these skills have a habit of being passed down at the “eleventh hour”. He’s seen the cycle of ageing stonemasons who realise they need to pass on their skills just before they retire – indeed, they were his teachers. That said, he’s only had three apprentices of his own in 20 years.

“You can’t learn this stuff from a book,” says Ted. “You need to sit there and watch and watch…”

The eleventh hour must be pretty close; let’s hope TAFE sees a mad last-minute rush.