Timothy Alouani-Roby: Please tell me about this exhibition Poetica, as well as the wider collaboration with WonderGlass.

Vincent Van Duysen: Well I’ve known Maurizio, the owner of WonderGlass, for many, many years… Professionally, we’ve been through other collaborations and we’ve been big admirers of each other’s work. We’ve been trying to make this collaboration happen already for a while. So, I would say that these objects are the result of a momentum that we’ve chosen [in] going forward together with this collection, which basically is from not even a year ago.

Within the sense of ‘Poetica’ and then my collection’s name, Optô, I think they reflects also a little bit about where we stand, where we are in the world – and where we need [to be]. So, I think it’s really the right moment to present this collection to the world.

You’re an architect and you’ve described these objects as having an architectural essence. What’s the connection between your wider architectural practice and those qualities that you see in these pieces?

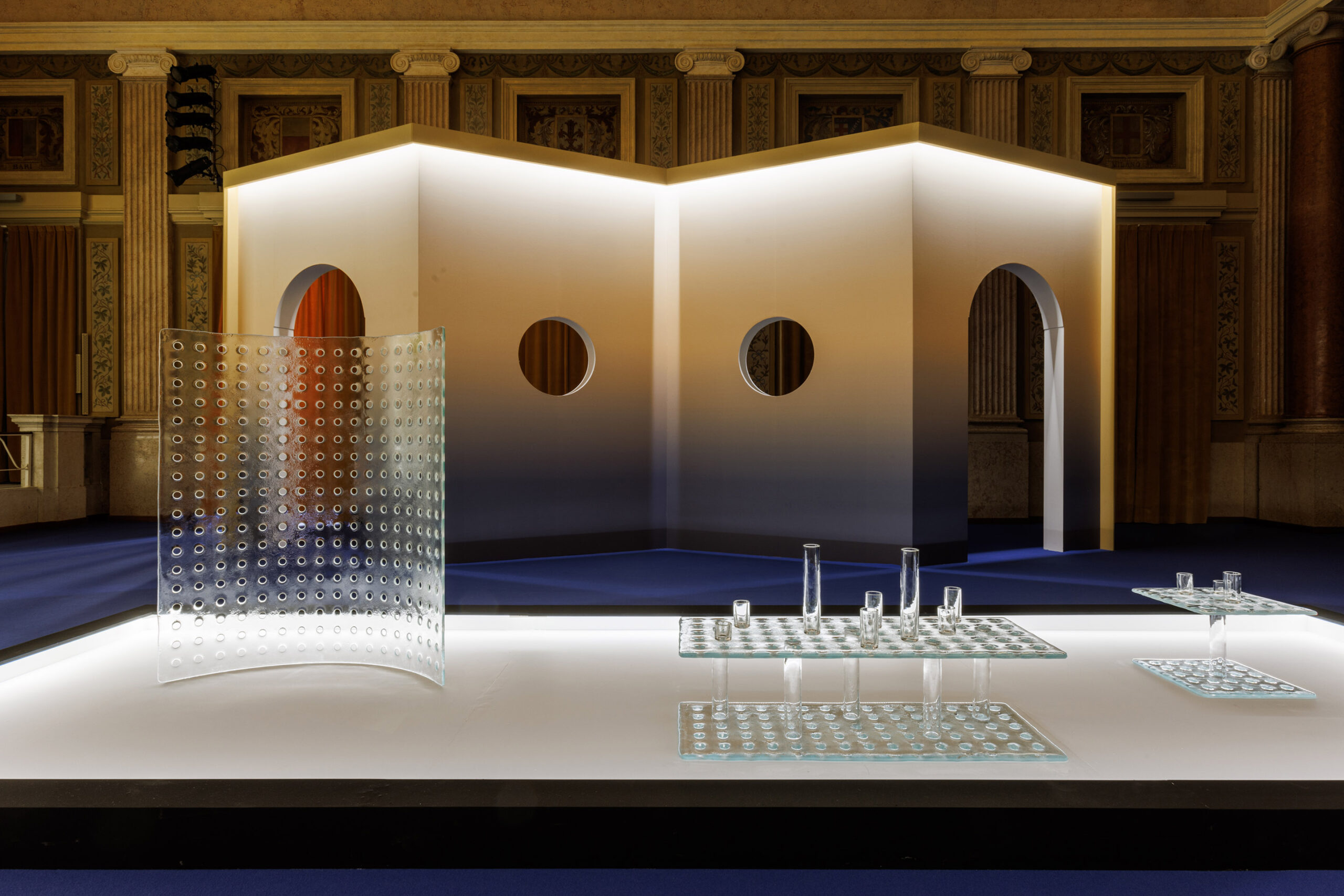

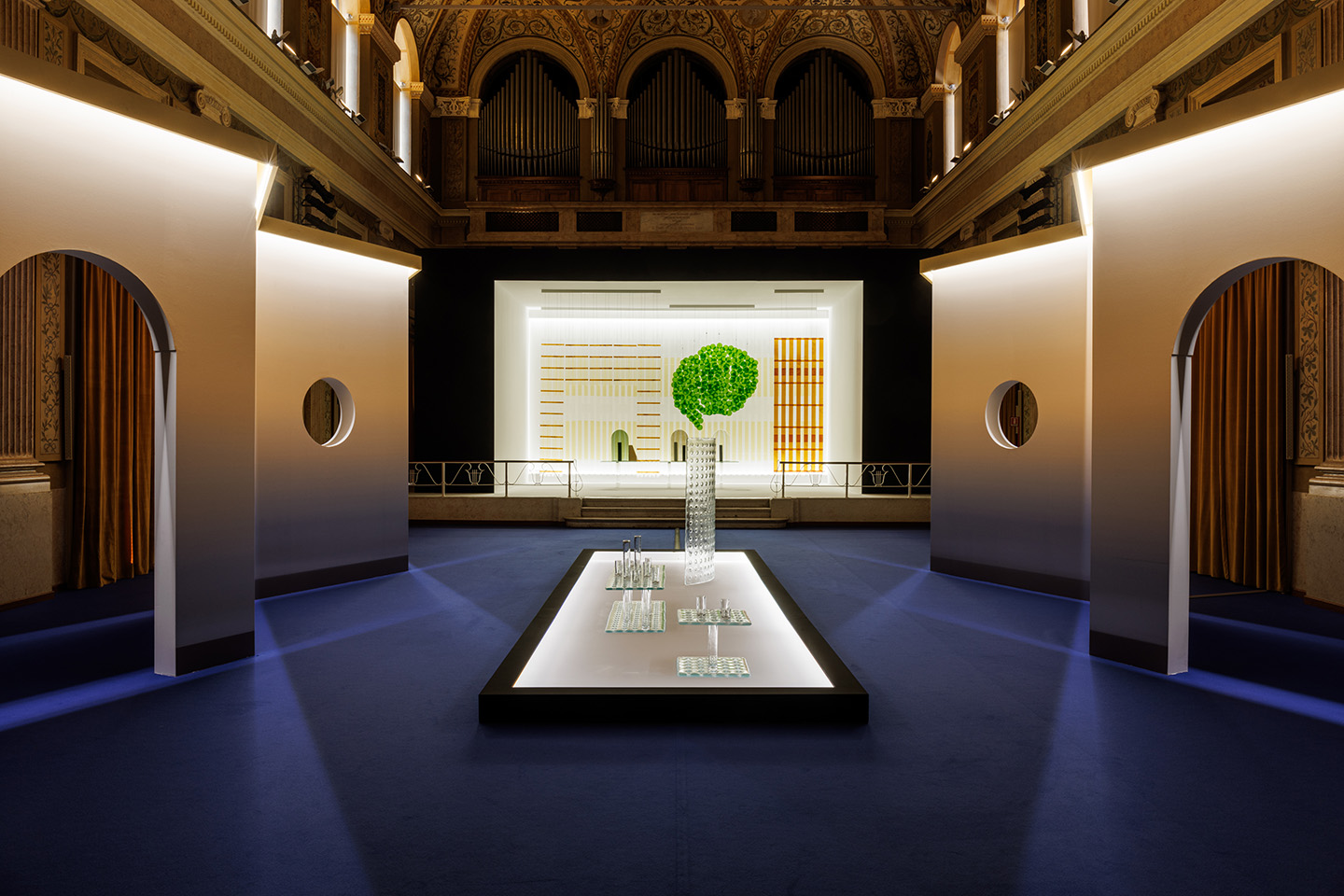

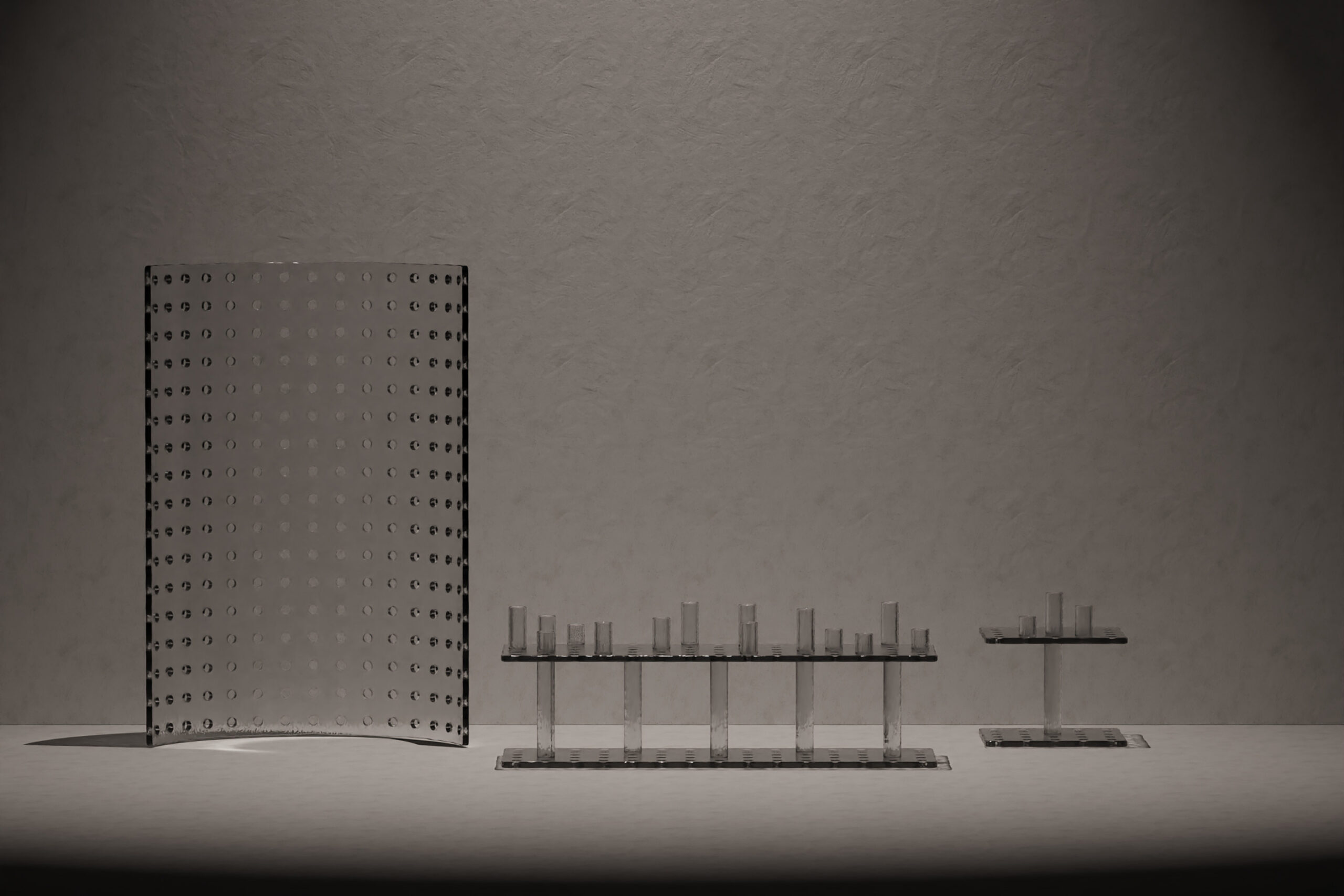

These kind of pieces… I name them almost like domestic architecture. I mean, you can see the way they’re constructed – it has an architectural eye. I’m not going to say that these are little micro buildings, but, still, you can see that the various elements are related to the world of architecture, and that we basically compose and build up these kinds of pieces with a mindset of being an architect.

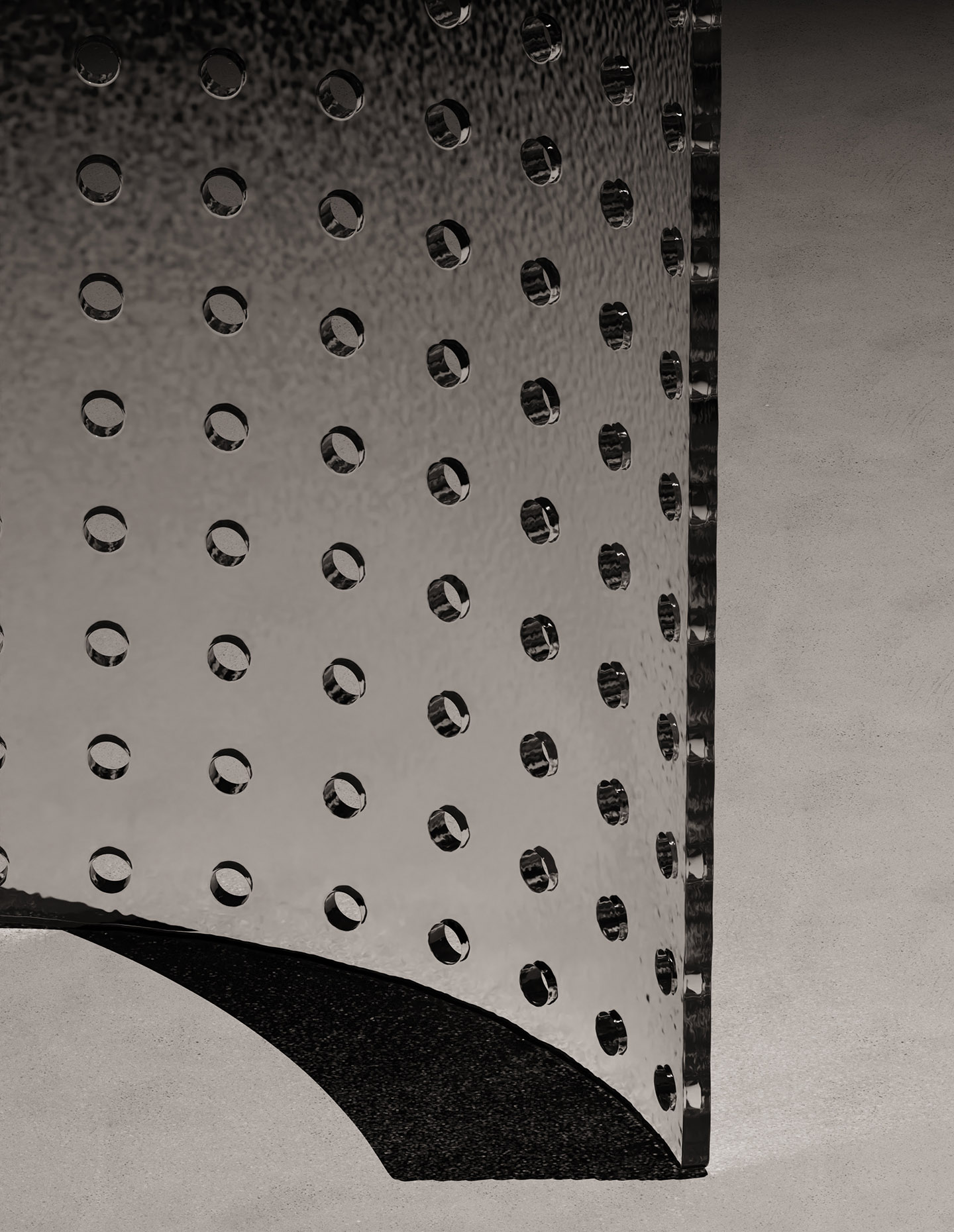

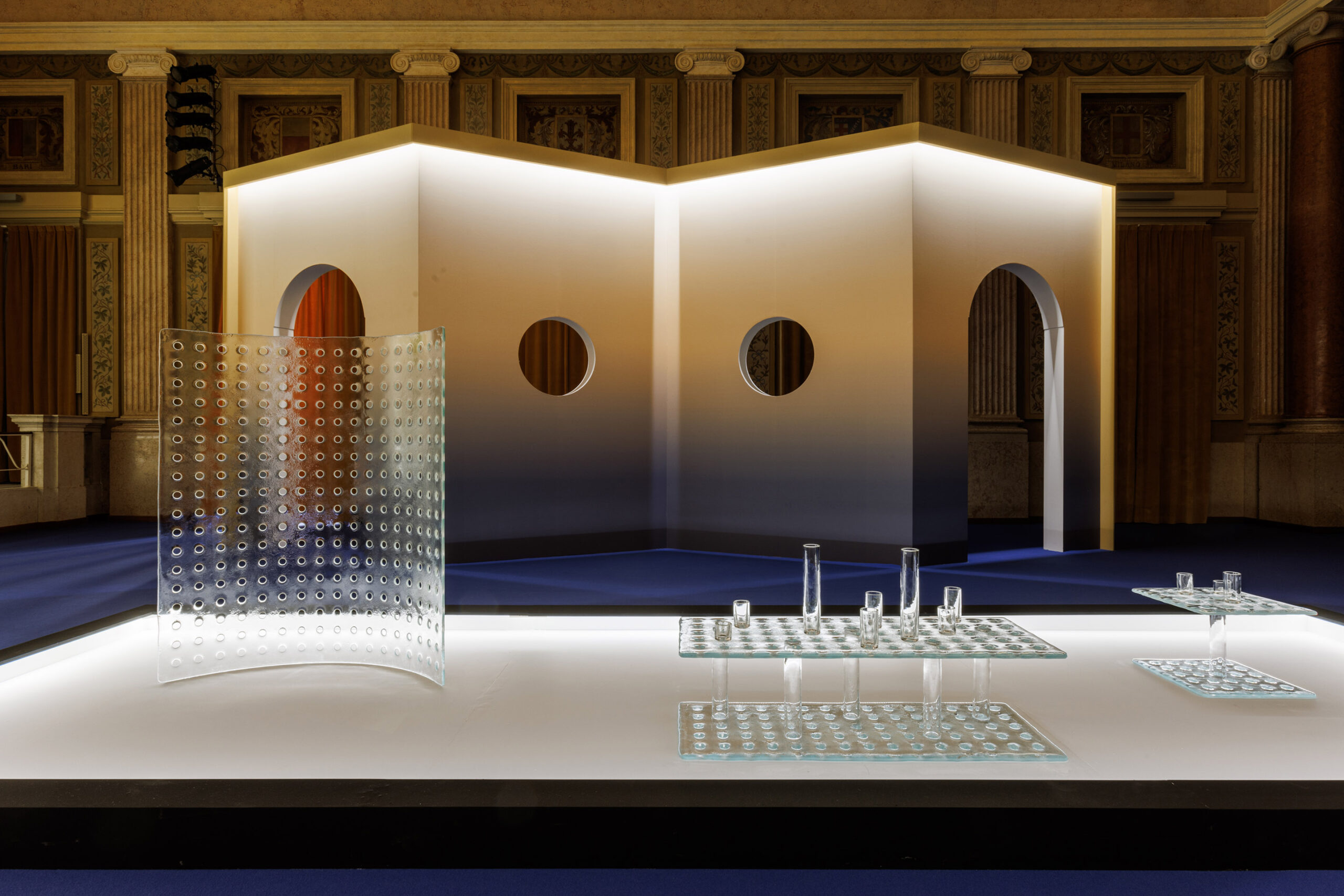

Glass, in architecture, we only knew for partitions or for windows. Here, though, I really wanted to use and implement glass as a more ephemeral, light material. There’s a juxtaposition between opaqueness and transparency, [while] the beauty of the imperfections and the irregularity are also very important.

It’s fused glass for the tops and the basements, and then the blown glass tubes that recall pillars [in the sense] of architecture. They are holding those plates where we can create little side tables, but they can also contain water with a vase or an object or a flower in it. It’s very… dual!

Of course, the perforation itself is where it comes from, from optǒ, because optǒ comes from the Greek – it’s terminology from ancient Greek where it stands for an opening, a gap. And an opening can be also very suggestive and very symbolic; it can be an opening to a new world, but it can also be an opening to a new beginning. It can be an opening to bringing light. I think these kinds of symbols are also then brought within the conception of these projects.

I think there is also a relation between shadow and play, which I really like. The shadow and the light are these elements [that are] are interconnectable and you can read them all in these pieces, and in this space especially.

Is there a tension there between the qualities of these objects in isolation and reading them in terms of the context that they’re in – this room, for example?

For me, not necessarily. All of these pieces or products that we design, they’re always in a relation with the space where they belong, so there is of course a relation between the space, the architecture and the object itself. What these pieces particularly evoke is a form of stillness, a kind of silence – something which we all need and which we all want now. We’re living in a fast-track world, so we also need objects that are making people dream where, there are moments of stillness, of silence, of contemplation.

It’s already something that you see in my architectural work, and it’s something that I wanted to bring in also with this collection. It’s also the reason why I didn’t want to use colour, because I didn’t want to have any kind of visual distraction whatsoever. These pieces are very dreamy and they belong in any kind of space, but, ultimately, they’re very solitary pieces and they’re living quite their own lives within the space where they belong.

Can you tell me about the process of crafting and making the glass?

The tops and the basement are fused glass, so basically there are two plates of glass that are fused together while they’re doing the perforations. And then they’ve got this irregular, fluid effects of glass – it’s almost like still water. You can see where the columns of the bases and little vases are blown glass, [which is] more traditional. Everything, of course, belongs to the tradition of glass manufacturing that you see a lot in the area of Venice, but in a very artificial way.

We also met Jaime Hayon in Milan this year – read the full interview here!