Sixty-six Hunter at Bligh is the site of a most notable Art Deco building. When the scaffolding came down in 1936, Emile Sodersteen’s 12 storey City Mutual tower was crowned Sydney’s tallest skyscraper. The stoic granite façade, its black marble lobby, Rayner Hoff’s copper bas-relief above the entry riffing off Benzoni’s ‘Flight from Pompei’, everything marked it as a building apart. Today it’s notorious as the headquarters and flagship of the Rockpool Dining Group.

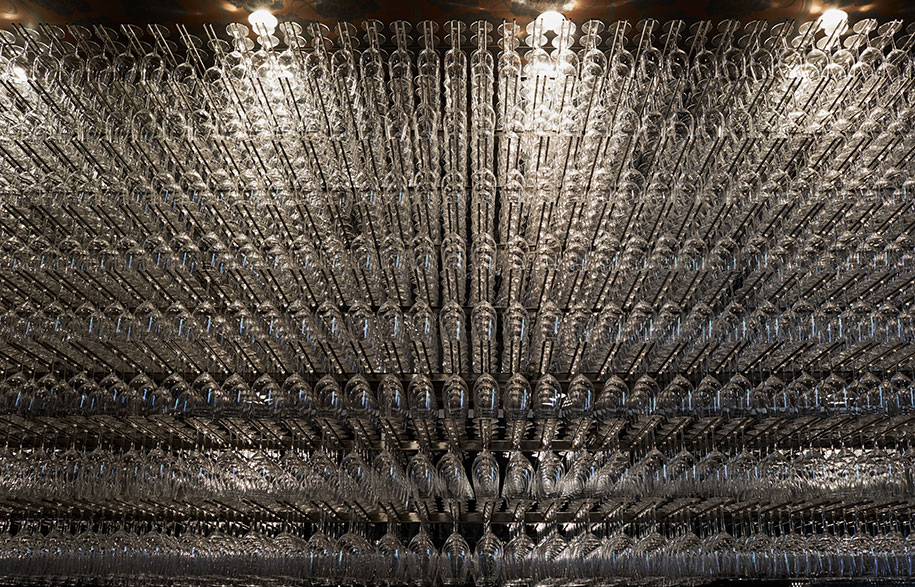

As I clamber up the dozen or so marble stairs the tinkle of cutlery and stemware rolls out on breakers of glamour. Bevelled scagliola columns, green veined as fine Roquefort, rise to the triple-height ceiling as light filters in through tall, lead trimmed windows. But my destination’s not in there with the fine diners, not this time. This time I’ve been summonsed ten flights up to appear before the admiral of the Rockpool fleet, Neil Perry.

In truth, I’ve known Neil for nigh on 30 years. As a young man trying to save up enough money to move to Paris, I got a job as a waiter at the first Rockpool, on George Street in The Rocks. It was 1989. Lunch was still a tax deduction and the crash of ’87 old news. The stock exchange was ravenous and all those Golden Boys, the young wolves needed somewhere to lunch. At Rockpool the Cristal flowed freely, as did the Château d’Yquem. The mudcrabs were so enormous patrons had to wear bibs to protect their Armani suits, men and women alike. But what was most extraordinary about that first Rockpool was the unabashed extravagance of the interior. A high temple to post-modernism devised by D4 Design’s Stephen Roberts, Bill MacMahon and Michael Scott-Mitchell, the bespoke up-lights were like silver satellite dishes transmitting diners’ magnificence. The gradated incline of the central ramp was a catwalk upon which the great and good could strut. Michael Hutchence slinked up it with Elle Macpherson, then with Kylie Minogue, then with Helena Christensen. Barry Humphries ambled up there, as did Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Kevin Costner and Bill Clinton. Gough Whitlam ascended its heights, to be followed in quick succession by Malcolm Fraser, Bob Hawke, Paul Keating and John Howard. Everyone, but everyone wanted to be seen at Rockpool.

“It was genuinely exciting to walk in there,” remembers food critic and author Jill Dupleix. “It was so theatrical, so glamorous, there was such a grown-up feeling about it. It was unlike anything that we’d ever seen in Melbourne or Sydney before. There was this immediate buzz. You actually did have to think seriously about what you were going to wear.”

A few months before our meeting at 66 Hunter, in November 2016 Neil Perry confirmed the merger of his Rockpool Group with Urban Purveyor Group, a publicly traded entity backed by Quadrant Private Equity. American billionaire Greg Doyle relinquished his shares in Rockpool in the same deal, as Neil and his long-term business partner (and cousin) Trish Richards stepped up to executive positions on the board of directors of the newly christened Rockpool Dining Group. Add in the fact that Neil is also celebrating his 20th anniversary as creative director of food & beverage of Qantas, responsible for what goes into the stomachs of millions of passengers a year, and it’s safe to say that Neil Perry is the chef most Australians are likely to encounter at least once in their lives. It could be inflight, bound for one of Qantas’ 200 destinations around the world, eating beef from Neil’s own Cape Grim cows at one of the many Burger Projects across the country, or at any number of Saké or Saké Jr outlets – just some of the UPG operations Neil has taken under his expansive wing. Or it may simply be in the food hall of David Jones where he is busy overhauling the food & beverage offering of the world’s oldest department store.

ST: Neil, so what exactly is your title

these days?

NP: Executive Chair of the board, Head of Culinary, Brands, Marketing and Training for Rockpool Dining Group. There’s the CEO, CFO and myself, on a line.

ST: Gone, the long services slogging it out

over a hot grill?

NP: Mate, the way I look at myself, I have different parts of my career, but at heart I’m a restaurateur. I’ve had a large part of my career weighted in cooking and food, and I suppose that’s what I think is my great ability. I create menus that people enjoy eating. Some people are really awesome chefs but they don’t really create food that people want to eat.

The light up here on the tenth floor of City Mutual tower issues from fluorescents embedded in a false ceiling composed of acoustic tiles. The desks and partitions are made of timber composite, the air is still, the only noise the rapid-fire clatter of keyboards. Neil’s carrying first class baggage under his eyes, but strangely doesn’t look tired. If anything, he looks fired up. At almost 60 years old and 90 days into a new business deal that sees him at the helm of an empire, he’s not so much finding his feet as he is kicking ass.

His development plan involves 21 Burger Projects by the end of this year, between 50 to 70 in the country before long. A new seafood iteration of Bar & Grilled, called Wild to debut in Perth early 2018 ahead of national expansion. Rollouts of more Rockpool Bar & Grills across Australia. In effect, by integrating the various UPG outlets, Rockpool Dining Group will be leveraging 15 brands over 50 restaurants and “we could be at 80 restaurants in 2018,” Neil estimates. “For the next 10 years of my life I’m really excited about building this restaurant group to be not only one of the great ones in Australia, which it clearly is, but one of the great ones in the world.

“For years, I’ve focused on building upon what you’d call my brand. But brands are essentially a recognition point. I can’t build a brand, but you can tell me I’ve got one. You can tell me, Oh, I have the most incredible memory of eating at Rockpool Bar & Grill. So if someone says Rockpool, I think quality, I think great service, I think brilliant wine. I tell the kitchen and floor staff now, it’s really important for them to understand clearly what they do because it’s the emotional side that people want to buy into.”

ST: You tell the staff the message they

need to convey?

NP: Yes, at each level there’s a

different message.

ST: You didn’t tell us anything at Rockpool.

NP: Yes I did, but you were always on drugs and drinking my Champagne.

Times have changed since the heady 1980s, and along the way Neil Perry has had some fails. Restaurants have gone bust, partnerships fallen apart. But Neil, unlike many other restauranteurs around the world has not only survived, but thrived. Partly that’s due to his inherent understanding of the way a restaurant works. He began his career front of house in the early 1980s before setting his eyes backstage. Young, cute in a Yakuza kind of way and already sporting the trademark ponytail he wears to this day, he did a kitchen tour of the great Aussie eateries. “I spent almost a year working with Stephanie Alexander, Damian Pignolet, Gay Bilson, Tony Bilson. I started cooking around February and I launched out on my own at Barrenjoey House in November.” That was 1982 and Barrenjoey House, an hour’s drive north of Sydney is where Neil first started to make waves. By the time he opened the Bluewater Grill at Ben Buckler, North Bondi, in 1986 he was definitely one to watch. As Jill Dupleix remembers it, “Terry (Durack, her food critic husband) and I had come up from Melbourne, and we’d normally go to Berowra Waters Inn but we’d heard about this new place in Bondi and decided to go there for Sunday lunch. We got a table on the little balcony and ordered mango daiquiries, looked at each other and said, ‘So this is Sydney!’ Finally, someone was claiming our country, our land, our beach, our seafood, our backyard barbeque no bullshit style as a restaurant. Everyone was young and grinning and sipping mango daiquiries!”

Then came Perry’s at the corner of Oxford and Queen Streets, Woolhara, something of a cursed, mock-gothic Victorian folly (Philip Searle would later break his teeth on the same venue under the banner of Oasis Seros). “The lesson I learnt at Perry’s is never name a restaurant after yourself, at least not so early in the game. That’s really important for me, although great chefs like Gordon Ramsey and Guillaume Brahimi have done it. But with Rockpool as my company name, I still own the name Neil Perry and I can always do other things. If someone had’ve said to me back then, ‘You’re going to sell this business and create another,’ I would’ve said, ‘No way. Josephine [Neil’s daughter with his second wife, Adele Seagar-Perry] is going to have this business when I die.’ But then I realized I could actually build a bigger, better brand, a restaurant group with capital and shareholders.” Today, Rockpool Dining Group is that bigger, better brand with capital and shareholders.

Beyond his inherent understanding of restaurant as process Neil Perry has an evolved sense of restaurant as place. He has always excelled at creating memorable experiences – and he’s clever enough to know that means more than just what’s on a diner’s plate. It’s about the atmosphere in which the food is consumed, from the overture of entering the space to the entr’acte between courses to the coda of the final goodbye. His work with interior designers is testimony to that greater vision. D4’s radical configuring of that first Rockpool was otherworldly, off the charts. Stellar. Driven by the first Mrs Perry, Nicole Shrimpton, it’s the first time most of us had experienced Missoni jacquards padded as acoustic wall finishes, or a monolithic, bright yellow interior wall à la Louis Barragán. Or a loft-like oyster bar rag-rolled in murky blue-greens and shimmering silvers to recall the inside of a shell – in which the diner, to extend the metaphor, must be the pearl. Stephen Roberts’ iconic D4 Rockpool dining chair remains highly collectible to this day.

For the past decade, Neil has entrusted the elaboration of his dining rooms to one man, Grant Cheyne. Prior to establishing his own practice in 2009, Grant had worked with Philippe Starck then Andrée Putman in Paris and Takashi Sugimoto’s Super Potato in Tokyo. A period at Bates Smart, Sydney, lead him to Rockpool George Street during the firm’s recalibration of that interior in an attempt to capture a new dining public. The fantastical theatrics of yore were fine tuned to cleaner, leaner times, but nonetheless Rockpool closed its doors definitively in 2013. By then Grant and Neil had become partners in design.

“I’ve no title within the Rockpool Group,” says Grant. “I’m my own entity, I just happen to do most work these days for Neil.” Grant’s most remarked work to date is perhaps 11 Bridge, the restaurant only blocks away from the original Rockpool tasked with communicating a new message about quality dining in casual times. The decision to create an all-black “more New York loft than a New York loft” interior (Grant’s words) had immediate impact and garnered the space and the architect a slew of awards. Neil’s recent decision to shut 11 Bridge and reopen it as the best Chinese restaurant in the land has meant that Grant has needed to reimagine the space yet again. “What was all black is now going to be all white,” he shrugs. “Easy.”

Grant doesn’t just do the zwoosh, upmarket stuff. He’s hands-on with all iterations of the Burger Project, for instance, with its readily reproducible industrial aesthetic. (“Someone said of Burger Project that it reminded them of a Japanese carpark,” he relays with a laugh. “And I said, Perfect!”) as well as devising the suite of Saké offers from the ground up, at the same time as elaborating the inaugural Wild in Perth’s Burswood district which will be the template for a national rollout.

“Neil’s had some tough times business

wise in the past, and learnt a lot from that,” says Grant. “He has a lot of energy, a lot of ideas, and a great determination to show that he can do it. He’s loving the challenge of bringing these diverse dining experiences up to a better standard, putting them back on the right track.”

ST: What’s the process of working with Neil Perry like?

“He’s very good at doing a very succinct brief. He can explain to me in three sentences exactly what he wants. I respond to that and if it’s on track he’ll say, ‘I get it. Done’. For the new Wild restaurant, for instance, Neil said to me, ‘It’s about the best available, sustainably caught, regional seafood.’ So I interpret that it’s all about the essence. What wagyu beef was to Rockpool Bar & Grill, this extraordinary line-caught seafood will be to Wild. There’s something delightfully primitive about catching and preparing seafood. And I came back to him a few days later with the response: ‘It’s a bit like a really great restaurant in Santorini, isn’t it? ‘And he says, ‘Yeah, nailed it!’ So within a very short space of time we’re both on the same wave-length. What I brought to the table besides the Santorini idea, the warm and fuzzy on vacation vibe, was the idea of something really simple. Primal. For instance, the skeleton of the fish inspired me to do lighting and other textures based on filaments.”

Neil’s other collaborations with designers have been less terrestrial. Celebrating his two decade partnership with Qantas, this year is also the 17th he has worked alongside Marc Newson, whose critically acclaimed Skybed business class seat of 2000 segued into him designing the complete cabin fit out of the flying kangaroo’s fleet of Airbus A380s. “Neil has been pivotal to my experience with Qantas,” says Marc by phone from Tokyo. “Having a like-minded and experienced contemporary to work with has proved invaluable to so many aspects of my creative work for Qantas, from the very specific elements like crockery and cutlery to the greater inflight experience that we’ve worked so hard on.” Neil refers to Marc as “a colleague and friend”.

“The great thing about Qantas is that it’s an incredibly loyal company,” says Neil. “I’ve been with them for 20 years, Marc’s been with them since 2000, David Caon worked with Marc on the A380 and now Marc’s passed the baton on to David to run solo. There’s longevity and between us we’re in it for the long haul to create memorable and lasting experiences for Qantas customers.” It’s that focus on continuity, longevity, consistency, that is making Qantas a global premium brand, as intrinsically authentic in the skies as it is upon the ground.

CAON studio is located in Surry Hills, Sydney. It’s a tight family consisting of David Caon, his wife Jermamie Holtz who is studio director and client liaison and project manager on the Qantas account, and a handful of design assistants (including a staffie called Bagel). The degree of focus, the level of attention, the dedication to excellence is the essence they distill in service of the national carrier. To hear them talk about the mechanism of the new Premium Economy seat they designed in collaboration with Thompson Aerospace or about porcelain densities, or about the texture and complexity of a blanket is to witness wholistic design in action. “What I most enjoy about our workshops,” says David, referring to his collaboration with Neil, “is the constant discussion about how we can progress the experience for the passenger. Even after doing it for 20 years, he’s very open minded and willing to experiment.”

Being open-minded and willing to experiment are the two tics that have lead to Neil Perry’s great success. He’s more than a restauranteur, better than a mere chef, greater than the sum of his own parts. When the dust finally settles on the Rockpool empire, we’ll be left with a massive bastion of incredibly well-designed, intrinsically thought-provoking establishments that encapsulate all the signs of their times.

Words by Stephen Todd

Photography by Anthony Geernaert

This story was originally published in Habitus #36, the Nourish issue.