Above: The house opens up to its surroundings, taking in valley views to the south and flowing into an outdoor dining area to the north.

Jeremy Wolveridge’s architecture practice is based in the inner-Melbourne suburb of Collingwood, famous nationally for its Australian Rules football team, but celebrated locally for its evolving mix of fashion houses, galleries, furniture shops and hipster-magnet bars. Of course, the journey of gentrification is far more exciting than the arrival and Collingwood still has a way to go: amongst all the urban renewal, a few of the factories still make things. It’s a fitting habitat for Wolveridge. His practice’s signature innercity residential projects are characterised by a layered industrial aesthetic that responds to the architectural palimpsests found on site.

Wolveridge Architects also does a lot of work in tropical north Queensland and along the Victorian coast – locations where ‘response to site’ demands mindfulness, not so much of architectural and social history as of the natural environment. But, despite this disparate grouping of architectural project types, common themes and ideas echo throughout the practice’s folio. This applies to the architect’s own house, even though, somewhat perversely, he eschewed both sea and city when choosing where to live, instead staking out 20 rugged acres of farmland near Kyneton, a little over an hour north of Melbourne.

In many ways, the Hill Plains House has been designed as one element in a scene: the house sits on a ridge overlooking a large dam and bushland to the north, and undulating grazing land to the south. More than 700 native trees have been planted to create a wildlife corridor along the north-western property boundary, and two rows of Maple and Crab Apple saplings, which fan out in a gentle curve away from the house, have been arranged to mark the landscape with distinct autumnal stripes of red and yellow. The driveway – cut into the existing ridgeline under the guidance of the architect’s father, acclaimed golf course architect, Michael Wolveridge – describes a single majestic arch that leads visitors to the southern side of the house.

The warm yellow of a floating kitchen joinery unit provides a counterpoint to the prevailing dark colour palette and raw textures inside the house. Blackbutt island bench top from Steptoes, Collingwood.

The warm yellow of a floating kitchen joinery unit provides a counterpoint to the prevailing dark colour palette and raw textures inside the house. Blackbutt island bench top from Steptoes, Collingwood.The building is intentionally naïve, its eaveless gable-roofed form and weathered timber materiality was inspired in part by a Victorian-era shed a few kilometres down the road that Wolveridge had long admired. Beautiful largely by accident, the old barn’s honest symmetry is thrown off balance by windows and doors positioned for accessibility and functionality. The Hill Plains House plays on this idea of asymmetry within symmetry: its southern elevation has a single large window at each end, lower than expected, and one wider than the other; full-height sliding glass doors in the middle; and a glazed, smoky-mirrorclad enclosed porch that protrudes from the façade. The porch is unmistakably Modern, a deliberate transgression from the rustic, and, as the entrance to the house itself, signals to visitors that the interior may indeed be more Mies van der Rohe than Massey Ferguson.

Needless to say, the house is infinitely more refi ned than the old barn; with mitred joins at the corners giving the outer shell a seamless finish, it’s more handcrafted box than timber shed. The lineage, however, is undeniable, and it draws out the first link to Wolveridge’s oeuvre. The Hill Plains House represents an intersection between historical, vernacular architecture and 21st Century residential design; old and new overlap, and the line between residential and non-residential form and materiality is blurred.

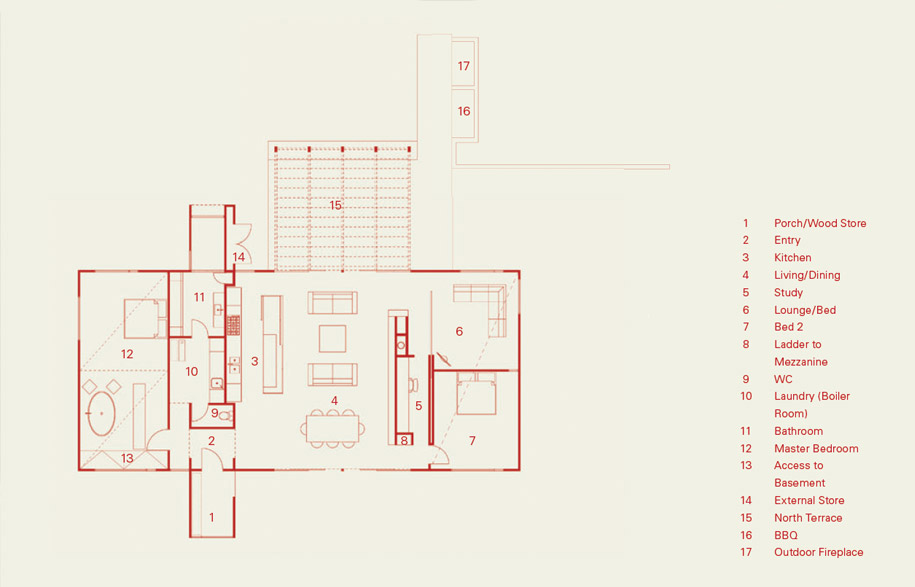

Programmatically, the house is relatively simple, but offers flexibility for the future. (This became increasingly important as the design process progressed – the project commenced as a bachelor pad but was eventually completed as a home for a young family). A services spine, comprising bathroom and laundry on one side and kitchen on the other, provides a buffer between the master bedroom at the south-western end of the house and the central living zone; at the opposite end, a blade wall clad in hundreds of timber off-cuts conceals a narrow study area, which, in turn, provides separation from the second bedroom and adjacent media/guest room.

The front of the blade wall, clad in irregular timber blocks, combines rusticity with a strong sense of order, much like the house itself.

The front of the blade wall, clad in irregular timber blocks, combines rusticity with a strong sense of order, much like the house itself.Adding the study came at the suggestion of Wolveridge’s wife, Christina, also an architect. It necessitated a commensurate shortening of the living area, but allows Wolveridge to work from home regularly. Christina also suggested constructing the house’s perimeter walls as reverse brick veneer, to provide extra protection against the often harsh weather. The resulting exposed internal brickwork adds to the interior’s warm, textural ambience.

The shower projects out from the southern window, framing a view of a gnarled Gum tree.

The shower projects out from the southern window, framing a view of a gnarled Gum tree.Indeed, the bricks, the smoky mirror panels, the timber off-cut blade wall and the dark-stained messmate strips that line the pitched ceiling over the living area, all reflect Wolveridge Architects’ rich, tactile sense of materiality. These interior surfaces are also quite dark, intentionally so, as this intensifies the effect of the outward views, drawing occupants’ attention to the hills, trees, water and sky outside. To this end, windows and doors have been positioned to maximise their effect as apertures to the landscape: the full height window to the shower frames a view of a monumental old eucalypt; the enclosed porch is a vantage point for watching the weather roll up the valley from the south; and the window to the second bedroom is low and wide, to capture the best possible view of Mount Macedon to the south-east. Even the sliding timber window shutters fixed to the building’s outer shell on the northern and western sides have been designed to filter light rather than block it completely, keeping the interior cool while preserving outward views. And the positioning of the house – on the ridge line rather than tucked into the hillside – was determined to achieve the best outlook in all directions. Clearly, the Hill Plains House has more in common with Wolveridge’s tropical and coastal houses than may be assumed from first impressions.

Left: A bathing area adjacent to the master bedroom references the architect’s tropical Queensland pavilions.

Left: A bathing area adjacent to the master bedroom references the architect’s tropical Queensland pavilions.Right: With window shutters slid open, northern sunlight streams into the master bedroom, mitigating the need for heating in winter.

Building the house atop the ridge also created scope for outdoor spaces to the north and south; the large outdoor dining area to the north enjoys winter sun and is protected from the prevailing southerly breeze, while the patch of lawn to the south provides shady respite in summer. Sitting here, looking down the valley that guides the eye to Mount Macedon, it’s easy to see what Wolveridge loved about the place. And, after all, ‘love of place’ – whether site of human history or natural environment – is the unifying theme at the heart of Wolveridge Architects’ varied output. The Hill Plains House, then, is at once the architect’s home and an emblem of his practice.

Photography: Derek Swalwell

derekswalwell.com

Jeremy Wolveridge Architects

wolveridge.com.au