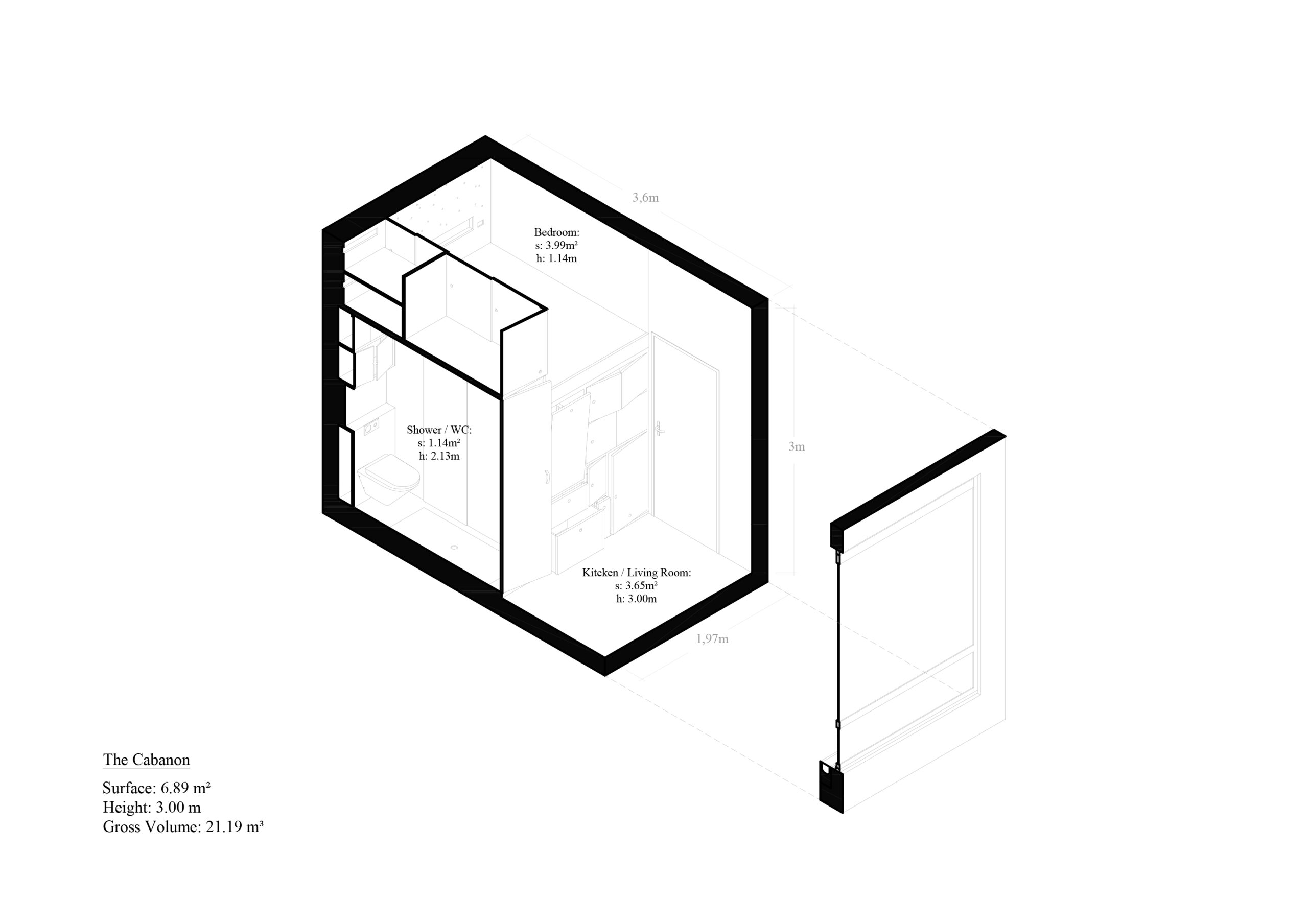

The Cabanon, named after Le Corbusier’s eponymous cabin in the Côte d’Azur, is a replete apartment measuring just under seven square meters. Positioned within a 1950s residential building in the heart of Rotterdam, it represents a conversion of a former storage attic into a living space, vying for the title of the world’s smallest fully functioning apartment.

It’s worth noting the constrained dimensions and austere parameters that would typically discourage designers. However, STAR and BOARD were challenged to think outside the box about the possibilities within such limited space. The apartment stands three meters high, shy of two meters wide and spans less than four meters in length.

The project was designed by the architects who will use the space, who go by the name of Beatriz (STAR) and Bernd (BOARD). The couple increasingly saw personal growth in voluntary reduction, configured the aerie to be autonomous, and prioritised their needs when considering each design decision.

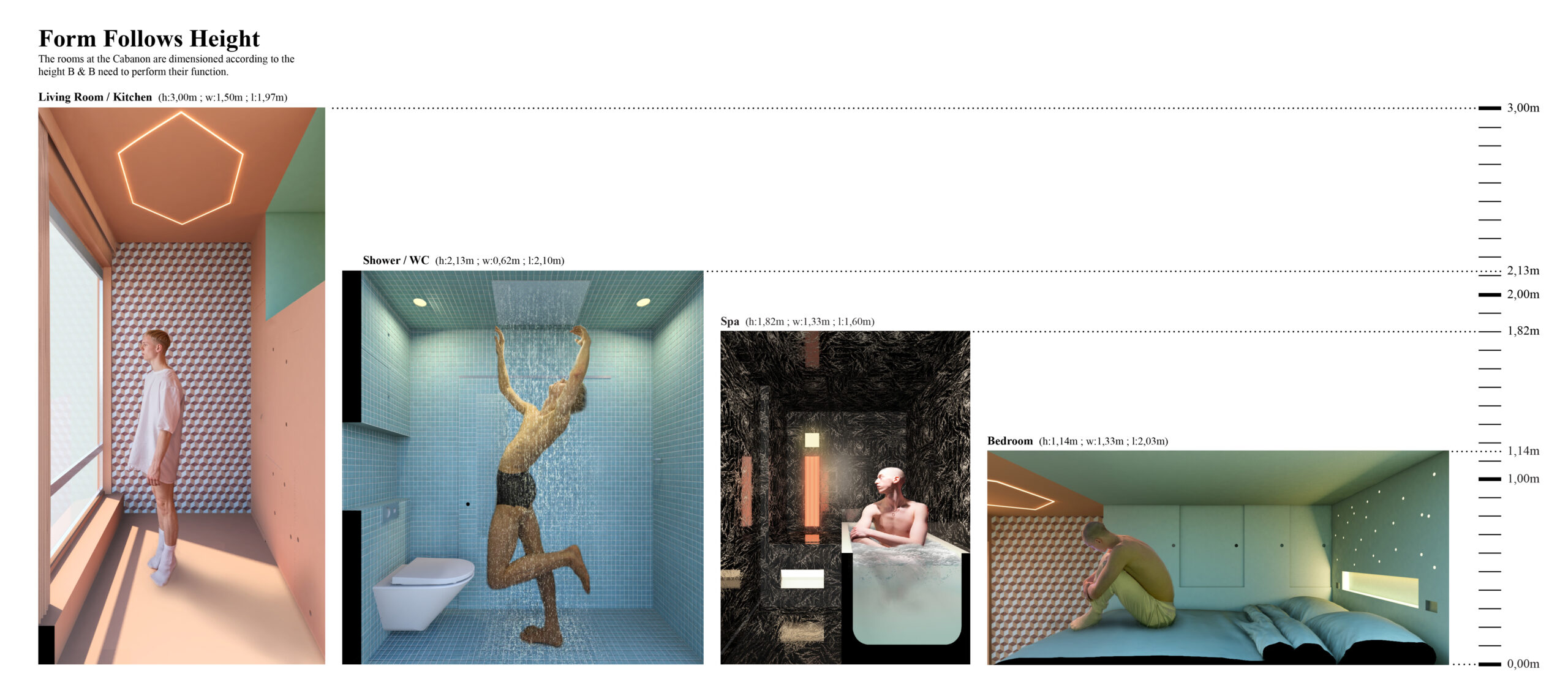

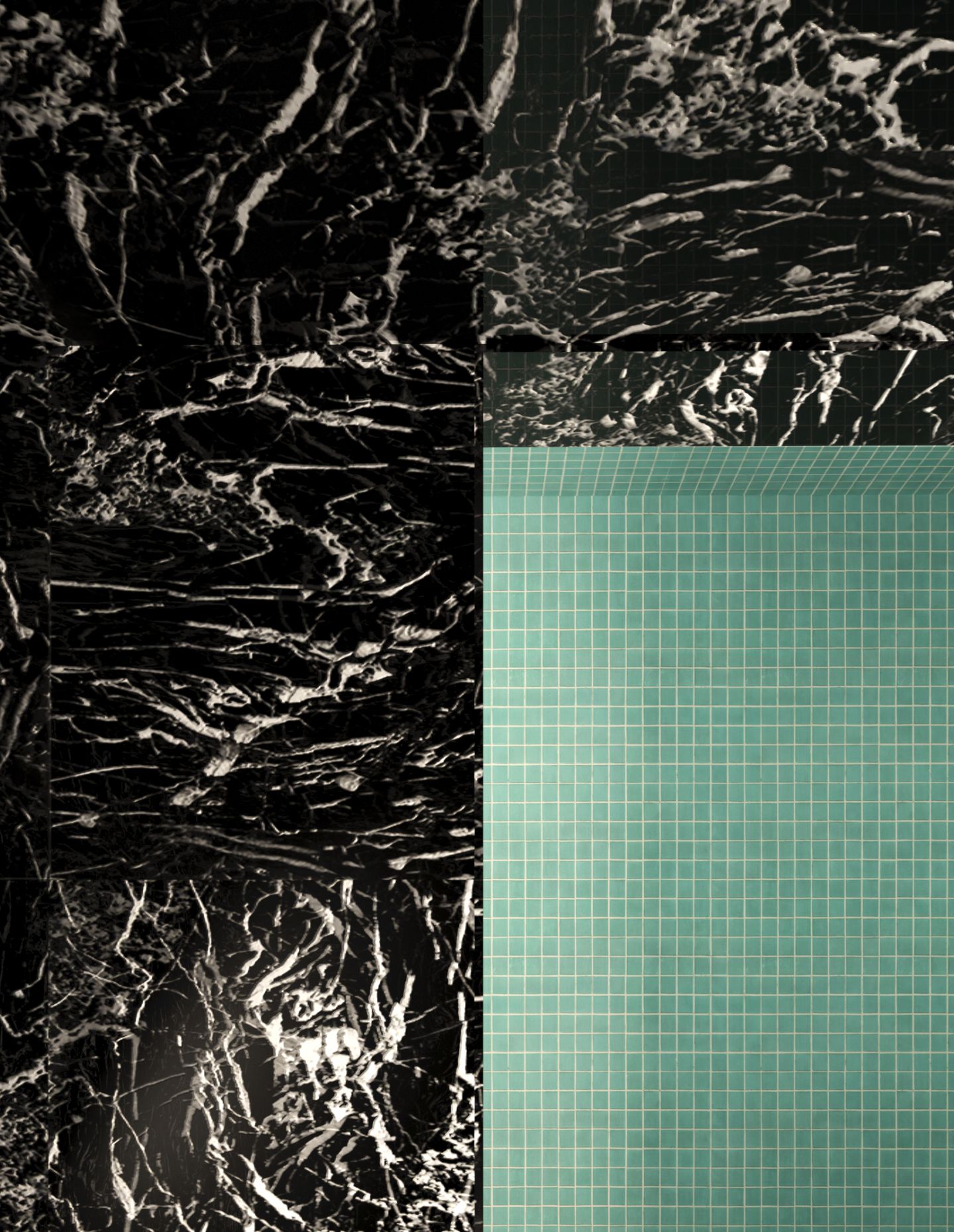

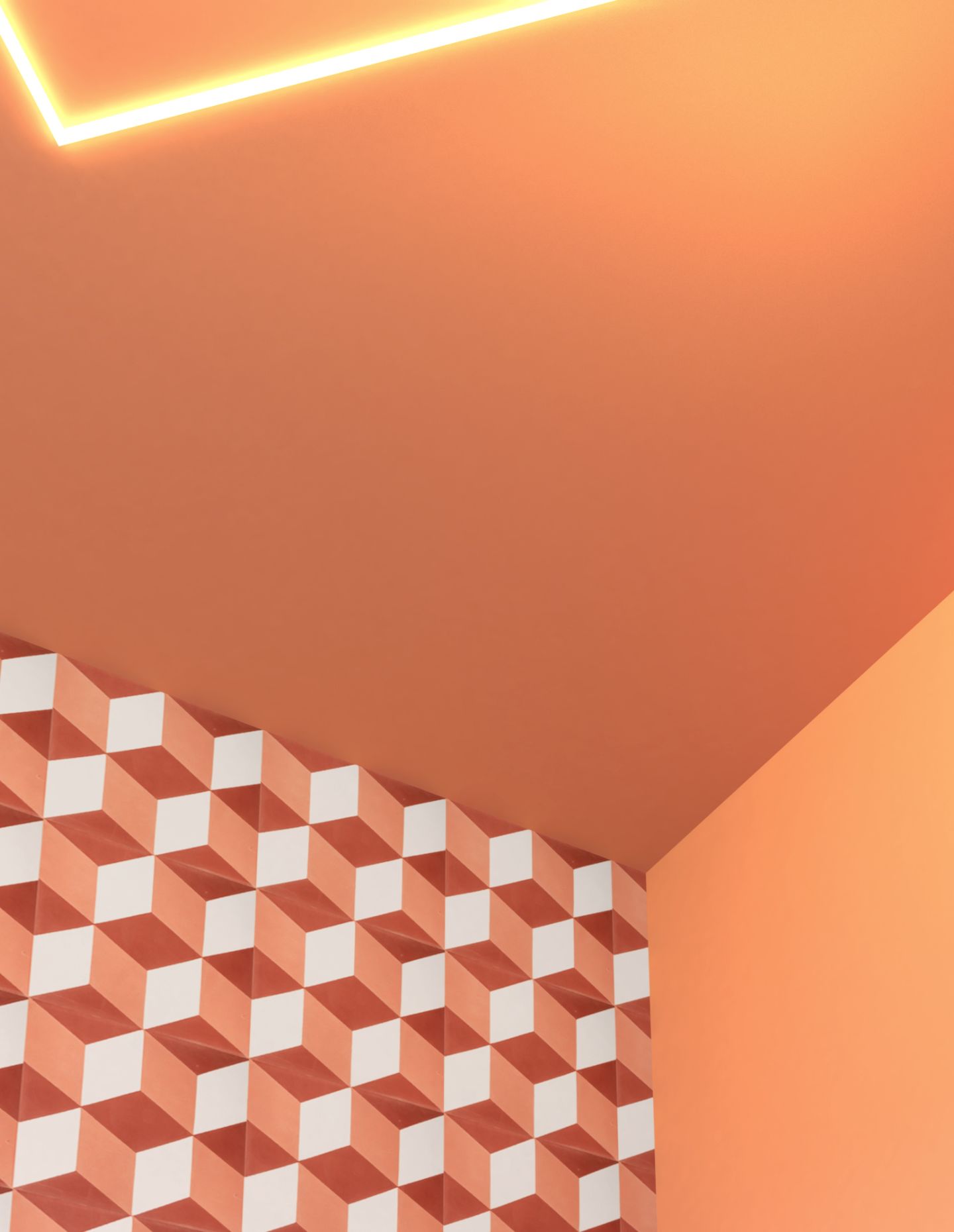

The intimate apartment includes a bed for rest, a bench along the window, a kitchenette (considering the couple’s preference for dining out on the weekend), a rain shower, two infrared saunas and a whirlpool bath. The Cabanon is divided into four distinct spaces, each delineated by varying materials and heights.

Typically, major constraints like regulations, time, budget and space shape a project’s design. However, Cabanon was exempt from two of these: regulations and time. While budget and space were limited, the restriction of space was longed for as a challenge rather than a constraint. This project demonstrates that adequate time, limited budget and space need not inhibit creativity. By relaxing regulations and applying common sense, radical innovation can flourish.

The Cabanon is scaled to the proportions of its owners who became the modulors, pace Le Corbusier, of their Cabanon. The spaces are dimensioned according to the height and width that Beatriz and Bernd need to perform everyday routines and daily functions. The serious consideration of spatial use and custom joinery should be used as a precedent.

The Cabanon transcends housing space regulations and was designed solely on logic and requirement, without compromising leisure. The Cabanon could help in optimising housing and costs but in no way does it advocate towards the reduction of surfaces as the only strategy towards affordable housing, nor does it pretend to be the “house of the future,” according to the designers. However, we can extrapolate some of its strategies in order to make current housing production better and cheaper. For example, “the optimisation of space – optimisation not understood as ‘reduction’ but as ‘maximisation’ of the possibilities of one space; the modulation of heights of certain spaces in order to superpose some functions; and the detachment towards possession and consumerism, so we are less inclined to buy and accumulate useless objects that clutter our houses (and minds).”

With Australia entrenched in its own current housing crisis, perhaps we can use The Cabanon as a prompt for optimising housing and costs, and challenging designers to consider and rethink what is necessary for everyday living.